A Quiet Obsession

David Eddington and His Passion for Painting

“I’m rather cool about my obsession. I don’t get all sweaty and enthusiastic.” — David Eddington

I can’t remember the first time David Eddington and I started talking — maybe it was the fourth or fifth time we saw each other at our local café in Venice, California. It was the height of the pandemic, and outdoor spaces were all we had. Every morning, I’d bundle up and go there to write. Eddington was one of the few other morning diehards — he’d be there no matter how frigid it was (yes, even Venice gets cold in the winter). While I typed away at my laptop, he’d sit nearby, sipping coffee, sometimes alone, sometimes with friends.

Eventually, we started talking. Maybe he asked me what I was writing. Maybe I asked him what he did. When he said that he was a painter, I wasn’t surprised. There was a quiet intensity about him, the kind that all artists recognize in one another at some level. As we talked over our coffees, I began to see just how deeply art was woven into his life.

“I’ve never done anything else,” he says. From as young as he can remember, being able to express himself with a crayon captivated Eddington. His path was cemented at age nine, when he realized, while marveling at the works of the Louvre and London’s National Gallery, that the only way to possess such beauty was to create it himself. And so he did — relentlessly.

It took courage for me to ask Eddington for an interview; he is quiet and thoughtful, not the type to boast about his work. The first time I brought it up, his answer was a hard “no.”

“Why?” I ask.

“I don’t think I’m passionate,” he responds.

“Of course you are!” I protest. “You paint every day.” By this time, I am aware of his relentless schedule — early mornings, marathon sessions, and an unshakable commitment to the work. It fascinates me how the most obviously passionate people are often the least willing to accept the label.

“I do,” he admits with a small shrug. “I’ve been doing it all my life. My journey is in front of the canvas.”

It took a few weeks, but I finally convinced him he was passionate enough for On Fire. We set a time, and at 9 a.m. on a Tuesday, I meet him at his studio, a bright, open bungalow surrounded by plants that wouldn’t look out of place in Jurassic Park.

“I’ve been up since 3:30 painting,” he says when I walk in the door.

Inside, I’m mesmerized. Paintings of every size fill the space — on walls, easels, and even piled on the floor. Paintbrushes are scattered everywhere. It’s the kind of clutter that feels intentional, like only an artist could make sense of it.

“Is that normal for you?” I ask.

“Getting up that early? Sometimes.”

“Yesterday,” he continues, “I got up at about 4:00, started painting at about 4:20, and I didn’t stop until 10:00 last night. Then this morning I’ve been painting virtually without stopping and without eating as well. At one point, someone phoned me up, and I suddenly couldn’t talk. I realized I hadn’t even had a sip of water.”

Eddington thinks about painting constantly, a hum beneath everything he does, never entirely switching off. “Normally people would wake up at 3:30 or 4:00 and groan and turn over I guess,” he says, “but I’m not very good at that. That’s probably why I get up: because I’m thinking about what I’m doing all the time. So I think, ‘What’s the point in lying here?’”

“And yet you claim you’re not passionate.”

“No,” he says, thoughtful. “In a funny sort of way, I’m obsessive. More than passionate.”

“What do you see as the difference?” For so many people I’ve talked to — from the psychologist Corey Keyes to my dad — the word passion itself trips people up. I’m always curious why.

“I’m rather cool about my obsession,” he says. “I don’t get all sweaty and enthusiastic.”

“So you see obsession as quieter than passion?” I ask.

“Yeah, like a meditative thing. Like me escaping into my own space.”

I think about his answer while I look at his paintings. I don’t know much about art; I loved to draw as a kid but stopped trying to improve after perfecting a few cartoon animals by age six. So I don’t have the technical language to describe Eddington’s work, which has been featured in galleries and museums across the world and often explores themes of industrial progress and environmental concerns. But I do know that I like his paintings. When I look at them, I feel something. They stop me in my tracks. That feeling lingers, subtle but under the surface, like a small shift in my worldview.

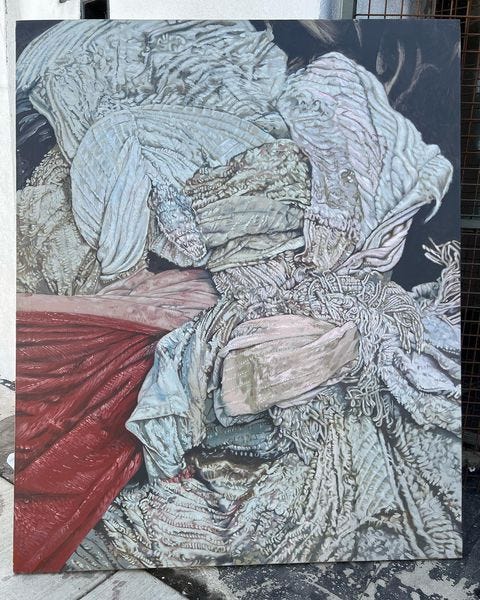

So, sitting in his studio, I skip questions about his techniques or materials — the things a more informed artist might ask. Instead, I focus on process and intent. I point to one particular painting — a large canvas awash in red, black, and gray lines.

“Tell me about that one?”

“That’s a bundle,” he responds.

“A what?”

“A bundle of rags.”

He explains how he began the painting in 1998 when he was a professor at Plymouth University. When he wasn’t teaching, he painted in a vast, empty hospital ward at Nottingham General Hospital, which had been repurposed as his studio. One day, he found a bundle of rags there and started painting it.

“I painted that same bundle for about 10 years,” he says. “That’s me being obsessive.”

For Eddington, it was never about the bundle itself — he never even unraveled it to see what was inside. It was about the act of exploring it again and again, finding new ways to express the same object, until the process itself became a kind of discovery.

“I only have one idea,” he says, matter-of-factly. “I just try and say it in different ways. I'm sort of just enjoying being alive, really — not looking for subject matter or anything like that.”

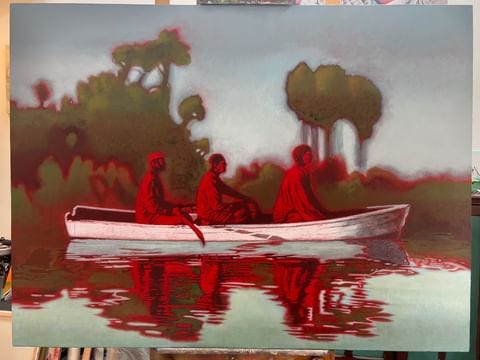

Another recurring subject in his work is the LA River, which reflects both his English roots — where rivers were lifelines — and his adopted home in California, where water represents survival and scarcity. He’s been fascinated with the river since he moved to the Los Angeles area over 20 years ago. He’s painted it, organized art shows around it, and has even sailed on it — there’s a boat on his back patio that he restores when he’s not painting.

I’m shocked when he tells me there are areas of the LA River deep enough to sail on. But here’s the proof:

Eddington says this about his work: “I like to keep it atmospheric and free. I don't want to spell too much out. I just want people to hopefully leave my work with a slightly different view on the way that they can look at things — without me telling them.”

The best type of art is like that. We find ourselves in the art, without the artist telling us what to think.

Eddington says his lifetime of art has been a search.

“What are you searching for?” I ask.

“I think it’s a way of me trying to understand.”

“The world or yourself?”

“My place in the world. Life is short and crazy. I like to think I’m part of something bigger, which is what gets me up in the morning. But I’m not going to say I’m part of any religion, Eastern or Western. I just feel that I’m trying to discover.”

And isn’t that what most of us are trying to do — trying to discover? This search is what drives him to paint and me to write. It’s probably what drives most of us at some level, whether you’re a more traditional artist or just a human being trying to navigate this crazy, beautiful, uncertain world.

Eddington believes more people should lean into that discovery.

“Life is so short,” he says. “You’ve just got to make the most of it. Make the most of your skills. Look at what you enjoy doing and try and do what you like. I think the world would be a happier place if more people could achieve that.”

Perhaps that’s passion. Perhaps it’s obsession. Most likely, it’s a little bit of both.

Links

Full Interview Transcript

Become a paid subscriber to access the full transcript of my conversation with David Eddington below!