“It's quite close to grief. Something has died. Except it's not a person… it's you. There's a part of you that's dying.” — Corey Keyes

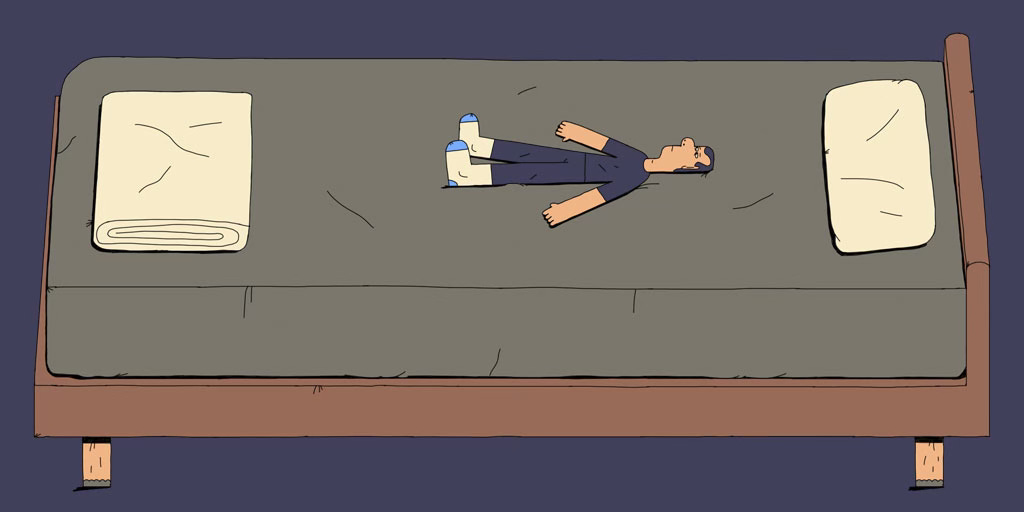

We’ve all heard it—that little voice within telling us something is just a little off. We’ve all felt it—life on autopilot, one day blending into the next… colors muted, feelings muffled, something missing.

It’s not depression. But it’s not happiness either. It’s something in between. Grayscale living. Languishing.

“Languishing is an alarm bell.. that something really good in your life gone missing,” says Corey Keyes, sitting in his home office. Behind him, a vibrant blue wall displays framed photos, a painting of a cat, and colorful abstract artwork. “And like many alarm bells, we often don't hear them. We turn it off and suppress it.”

Keyes is not just any positive psychologist describing this common experience—according to recent studies, the majority of people languish at some point in their lives. He’s the person who discovered this phenomenon, named it, and put it on the map. Long before Adam Grant’s 2021 article in The New York Times brought the term “languishing” into the mainstream, Keyes had been quietly studying what Grant called “the neglected middle child of mental health.”

And so this was not just any other interview. Keyes’s work is at the very heart of On Fire. In fact, my own personal quest to overcome my sense of languishing is what led me to find what’s emerged as my deepest passion—passion itself. I couldn’t just settle for a life that felt colorless. I couldn’t accept not fully living while I’m lucky enough to be alive.

And that in turn led me to start this newsletter and experiment in interviewing the world’s most passionate people—and creating a one-stop source of insight, tips, and reflections on living a passionate life. Keyes’s research has always spoken to me on a deeply personal level and, from the very start of On Fire, I knew I wanted to interview him. I was so grateful he accepted. But more than that, I was inspired when we spoke—not only to my surprise by insight, but also by his story.

Keyes’s fascination with languishing started young. He endured a dysfunctional childhood, he told me in our interview, marked by abandonment, addiction, and physical and emotional abuse by his father and stepmother. He spent much of it disassociating, a protective strategy that allows us to endure traumatic situations.

But when he was adopted by his grandparents at age 12 and went to live with them at their 55-and-over community, he was transplanted to a place of love and safety. “I was playing shuffleboard and hanging out with all these people and going to get the mail and talking,” he recalls. “I never knew life could be so good.” Almost overnight, he went from a struggling student always in detention to an honor roll student and athlete with good friends and a loving home.

It sounds like that’s when the story ends, happily ever after. But for Keyes, this is when life got even more interesting. Life was happier, but he wasn’t yet totally happy. Taking the bad stuff away, in other words, wasn’t enough. “I would come to the end of the day, so to speak, and stop,” he recalls. “It was like the room was empty.”

It wasn’t quite depression, which he did ultimately experience later in life. It just felt to him like something important was missing. He just couldn’t put his finger yet on what.

He pursued his curiosity into graduate school, becoming increasingly interested in what it means to have a mentally healthy world. But he found that most research focused on the two extremes of negative (illness, disease, premature death, death) and positive (well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, flourishing).

But what about the in between? That question sparked the lightbulb that is now fast changing the world—specifically, how we view what it takes to change a life.

Psychiatrists, he observed, measure and diagnose depression using nine symptoms; you must have five out of the nine to qualify. And to be flourishing, a different test says you must have at least six out of the eleven of markers of well-being.

So what happens if someone is just about down the middle—with a little of each? That, he observed, may be the case for most people.

“I wanted to take this picture and show it,” he says. “I wanted to say, ‘People, here it is.’”

But Keyes isn’t the showy type. In fact, he compares himself to a slow, methodical turtle.

“You've got to operate like the turtle. Be slow, methodical, do a lot of research, and then, at the end, while the hare is sitting there, arrogant and resting… say, ‘here's the science.’”

So he stayed quiet in the background, pouring over literature and engaging in research, diving deep into the human experience of feeling aliveness—or a lack thereof. He has had a profound impact on our understanding of mental health, particularly through his identification of languishing as a critical state between flourishing and depression. His pioneering dual-continuum model has reshaped how we approach mental well-being and wellness.

I’m so excited by all that Keyes’s work points to that I could have written an entire book on it. Luckily for you, he’s already written one—Languishing: How to Feel Alive Again in a World that Wears Us Down, the culmination of a quarter century of research.

Most importantly, I think you should get the book—and share it, as I have been doing, with everyone in your life who might be languishing. (You may find it easier to do than offering someone a book, for instance, on depression—languishing doesn’t have a stigma associated with it. It’s one of the most universal human experiences. It’s just not something to settle for.)

But until then, here are five strategies that I think will be of special interest to On Fire readers… and some personal reflections on each.

1. Don’t Just Subtract the Negative from Your Life… Add the Positive

There’s so much emphasis these days on self-care and removing unwanted things from our lives. While this is important, Keyes’s research shows that just subtracting negatives won’t make our lives magically better.

“The absence of the negatives does not mean the presence of the positive,” Keyes says, referring to his two-continua model of mental health, which shows that mental health and mental illness are related but distinct.

The key, though, is to not get stuck in the “I’m too busy” trap, Keyes says. Instead, add positive things that bring you energy and joy, including projects, activities, learning, and time with people that light you up. Soon, you’ll find the equilibrium will shift away from languishing and toward passion; new energy will create itself and low-energy parts of your life may over time fade away.

In my own life, this principle has changed everything for me—it’s hard to overstate its impact.

This is just one example: Before I became passionate about handstands, my life felt flat and rudderless. Handstands gave me a reason to get up every day even when I had nothing else going for me. That small addition of something I loved ended up being the catalyst I needed to pursue other things that I was curious about, helping me make the shift from languishing to flourishing.

2. Regularly Step Outside of Time

Most adults are tied to a clock. We time block our days with meetings, deep work periods, dinner dates, and appointments. This commodification goes hand and hand with an outcome-related mindset. “Time is money,” we think, determined not to waste any of it. All of this time pressure can leave us feeling anxious and struggling to breathe.

One of the best ways to break free? In his research, Keyes has identified five activities that can help us move from languishing to flourishing. He calls them the “five vitamins,” and one of them is to play more.

“It’s so generative,” he says. “It’s so good for growth.”

Play can mean different things to different people. It might involve going to the playground with your kids, having a board game night with friends, or participating in a pickup basketball game. For some, like my parents and Steve Paranto, pickleball is their ideal style of play; for others, like Matt Conwell and Pete Wharmby, it’s video games.

Play can come in other forms, too. Keyes and I both love the playful feeling that comes from talking about ideas with others on the same wavelength. “It’s improvisation,” Keyes says. “It’s joyful because it’s not emerging out of something that’s real.”

There is only one rule when it comes to playing correctly: it should be through active leisure. While there’s nothing wrong with watching TV occasionally, the ideal form of play involves engaging activities. And it means letting go of our time anxiety and growth-oriented mindset, at least for a little while.

“Forget the calendars and scoreboards,” he writes in Languishing. “Playing to finish or win is taking the external path. Even in play—spontaneous, carefree, without a goal orientation—we can attempt to maintain our allegiance to the internal path. Play for the sake of seeking delight, of letting one’s imagination run wild, of enjoying the freedom to roam—that is play. Perhaps play, in the end, is the most selfish of all our flourishing vitamins—and maybe that’s why it’s so hard for us to do.”

3. Tune into Your Imagination

Keyes believes that imagination—which allows us to envision possibilities beyond our current circumstances—is a powerful antidote to languishing. It’s not just for children, he adds. Adults benefit immensely from daydreaming, creative thinking, and visualizing possibilities.

“Imagination becomes another thing that’s very powerful in adulthood,” he says. “It’s the ability to think about possibilities and dream things that never could be, and then to pursue them."

It all started because you played with imaginary things,” he adds. “You made something that wasn’t real, real. That’s what dreams and goals are in adulthood. It’s just imagination applied to something different.”

I tap into my imagination through writing and by being creative in my workouts and jiu-jitsu training. These activities help me see beyond my current limitations and explore new possibilities. Plus, they’re just fun.

To cultivate your imagination, set aside time for creative activities that light you up. Whether it’s writing, painting, playing music, or even daydreaming, giving yourself permission to engage in these activities can unlock new ideas and perspectives.

Novelty and travel also help. By surrounding yourself with inspiring people and environments, you can tap into your imagination and begin to think more creatively.

4. Learn Something New

Another of Keyes’s five vitamins is lifelong learning. When pursued for personal reasons and interests, this kind of learning brings great satisfaction and fulfillment to our lives.

"Learning something new, of your own choosing, on your own time, for your own reasons is a surprisingly potent antidote to languishing,” he writes.

I couldn’t agree more. Learning new things or delving deeper into subjects I’m already familiar with brings me immense joy. I’m always reading, listening to audiobooks, or engaging in conversations with interesting people.

Many of us get bogged down with the forced learning associated with formal schooling. My mom loves to tease me and remind me that after I left high school at 17, I told her that I never wanted to learn anything ever again. Luckily, I snapped out of that a few years later, when I realized I loved to learn; I just didn’t like to be told what I needed to learn. One of the best parts of being an adult is that we get to learn what we want.

Keyes’s message is to embrace that.

What are you interested in? What have you always wanted to know more about? Take up a new hobby, attend workshops, or explore topics that intrigue you through books or videos. The process of acquiring new skills and knowledge can reignite your passion for life and provide a sense of achievement and purpose.

"Humans are just like everything else on this earth,” Keyes says. “We were planted here to grow. To grow and to explore."

5. Embrace Your Unique Style of Passion

Corey Keyes epitomizes passion; he has spent decades with almost monomaniacal focus making visible something that he believes with enormous conviction is one of the great challenges of our times and humanity in general.

But while he agrees that passion is key to feeling alive, he notes that passion can look different for everyone. Specifically, not everyone passionate needs to be outwardly exuberant.

“There are many times when you wouldn’t look at the way I’m acting and say I’m passionate,” he says. “And yet you don’t know it’s the magical world inside of thinking and ideas and math. It’s like a quiet turtle form of passion.”

I love that—and can relate. There are times when I’m visibly excited, talking nonstop about my passion—almost jumping up and down with joy. Other times, I may appear quiet and introspective, but the ideas are going nonstop in my head. Both are forms of passion; they just look different from an outside perspective.

Whether your form of passion is outwardly obvious or quiet and personal, Keyes says the key is to find what makes you feel alive and pursue it with dedication.

“It’s like a steppingstone or ingredient that you’re deeply committed to something,” he says. “And maybe this commitment is so much more than you. It goes beyond you. It becomes like a force that drives something outside of you. It drives you to act in the world.”

There is a sweetness to life,” he adds, “when we find something bigger and better to live for.”