“It’s okay to have short-term passions as well as long-term passions. And to be able to mix those together.”— Ross Hatton

It all started with a walking robot dinosaur. From the moment he came across the 18” high, four foot long robotic version of a Troodon dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period in the 2001 edition of the MIT News while a senior in high school, he was captivated — it was love at first sight.

“When I saw that, something twigged in my head,” recalls Hatton. “That’s what I want to be doing. I want to be looking at the physical side of robots.”

Before discovering the article, Hatton felt limited by the traditional scope of mechanical engineering, sensing that most mechanical problems had already been solved. But the article's depiction of a dynamic, two-legged robot rekindled his imagination and merged, in a flash, his interests in math, biology, art, and engineering.

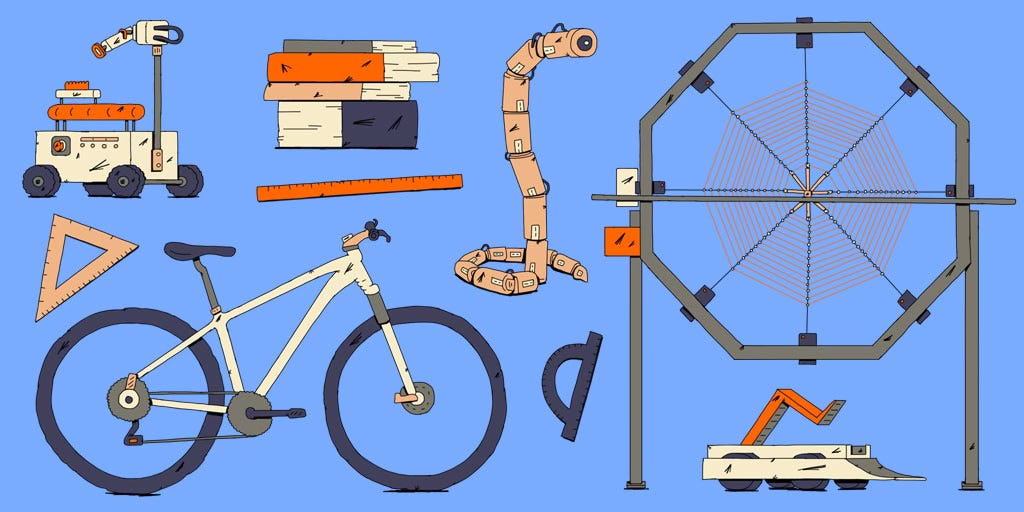

Today, Hatton is an associate professor at Oregon State University, where he directs the Laboratory for Robotics and Applied Mechanics. A 2017 recipient of the prestigious National Science Foundation CAREER award, his work includes the development of motion models for robotic snakes and fundamental models for the study of locomotion . All the while, he draws inspiration from all sorts of creatures — from snakes to spiders to, yes, dinosaurs.

I was introduced to Hatton through my nephew, Wyatt Boer, who studies under Hatton at OSU. I knew I wanted to profile someone in robotics — having witnessed Boer’s enthusiasm over the years, I’ve seen the passion and dedication that robotics enthusiasts embody.

“I think it’s the gradations between inanimate objects and life,” he says when I ask him what it is about robots that so deeply fascinates people. “Robots are somewhere in between there. They’re capable of more complicated actions than a simple inanimate object, but they’re not fully alive yet. Though we’re pushing them toward there.”

On top of that, Hatton says, is that in robots, “complicated emotion is visible. What a computer or a dishwasher or things like that are doing is fairly complicated, but they are in enclosed boxes. So you don't see all of that. With a robot, you can see how things are moving. You have some deep kinesthetic understanding of what it means to move in the world.

“Seeing all those pieces together… that’s what leads to a lot of that fascination,” he says.

This enduring fascination, sparked by the walking dinosaur in his youth, continues to drive all aspects of Hatton’s career.

“It really scratches both the itch of being able to do something in hardware and physically have it work,” Hatton says when I ask him what he loves about robotics, the science and engineering discipline concerned with the design, construction, operation, and use of robots. “But then also lets me go off and get as mathematically deep as I want to get.”

Hatton is known for his expertise in the complex math behind mechanical engineering, which involves solving problems about how things move and work. He’s been writing a textbook for the past decade to make these intricate concepts more accessible — though I have no doubt they will all still largely go over my head. Yet, unlike many of his more laser focused peers, Hatton thrives as much on the practical application as the theory.

“I teach both the most theoretical and the least theoretical classes in our graduate program,” he tells me. His courses (with names like: Snakes, Spiders, Robots & Geometry) encapsulate his philosophy: one dives deep into theoretical aspects of movement and mechanics, while the other offers a hands-on robotics experience that encourages practical application of their knowledge.

“I like to move like between the physical building, the math, the biology side of things, and the art side of things,” Hatton tells me. His students do too: “I'm quite happy when they go and take the tools we’re using and then use them to make art.”

When I ask Boer what it’s like to be in one of Hatton’s classes, he told me that Hatton’s passion is evident when he relates what they are learning about in class to his research: “It wasn't like he was bragging about how he did really cool things,” Boer says. “It was just him showing a really deep understanding about what he did and trying to help the rest of the class understand how it mattered.”

Boer’s use of Hatton’s math in his Robotics Club projects is a testament to Hatton’s approachable teaching style (sometimes I wonder how we could possibly be related — my brain just does not work this way).

Hatton's passion for interdisciplinary learning isn't new. Even as a kid, he gravitated toward many different interests — from books and mathematics to Scouts and cross-country running. Despite the underlying interest in robotics that has stayed with him from that day in his senior year of high school, Hatton compares his approach to a term borrowed from athletes: he cross-trains.

This is what he did when he first started working on snake robots, which marked another pivotal moment in his journey — one he describes as feeling “like coming home.” Initially captivated by the way snakes move, Hatton developed models and algorithms that enable robots to emulate these complex biological movements. He took his love of biology, robots, and math, and combined his areas of interest.

His cross-disciplinary approach became evident again when he initiated the SpiderHarp project. Fascinated by spiders and their intricate webs, Hatton collaborated with other scientists, biologists, and musicians to create a larger-than-life web constructed out of steel and orange parachute chord with a robotic spider to create a harp-like musical instrument, reflecting his combined interest in robots, spiders, and music.

And it showed up again when he partnered with a former cabinet maker to create composite bikes made out of wood. Hatton deployed his interests in design, materials, and mechanical engineering to help create bikes that offer an optimal balance of clean looks, strength, stiffness, compliance, and vibration damping — and are of course, fun to ride.

Hatton recalls realizing the benefits of cross-training as early as first grade, a few years into his chess-playing journey.

“I realized at some point that there were diminishing returns,” he says. “If I wanted to just keep playing chess and keep getting better at it, that time commitment would be cutting off other things. So not being afraid to say, ‘Okay, I’ve done this for a while, I don’t need to keep doing that. I’ve got that. I’ve got a pile of knowledge. I’ve changed the state of my brain. Maybe I can come back and do it again, but unless that’s the thing that I’m absolutely passionate about, then I can shift over to something else.”

I love this approach, and I tell him as much. It’s a reminder I often need myself. Too often, we fall into the trap of believing we must stick to one passion or path indefinitely. Yet, every choice to pursue something means another path goes unexplored. Allowing ourselves to delve deeply into an interest for a while, then permitting ourselves to shift our focus when our interests and priorities evolve, offers a more flexible way to engage with our curiosities over time.

For Hatton, robotics has remained his overriding passion through the years, even as he explores and expands upon his other interests. It intersects with numerous other areas, and he often finds himself moving between all these spheres, exploring how each can enrich and enhance his primary interest.

“It’s okay to have short-term passions as well as long-term passions,” Hatton says, “and to be able to mix those together.”

However, he cautions against merely dabbling. Instead, he advocates for a deeper, more deliberate approach: “Get deep on things and then pivot,” he advises, emphasizing the importance of thorough understanding before moving on. “Do things deeply enough that you really understand them… but maintain some flexibility and openness to go and do something else.”

“There’s benefit to depth — to having done something for a long time,” he adds. “But also not putting too much emphasis on thinking, ‘I should be trying to do this thing forever and ever’ is also important.”

Takeaways

Here is one big thing I learned this week about passion, one exercise you can do to stoke your own inner fire, and one aspect of Hatton’s intense enthusiasm that rubbed off on me — and that I now want to learn more about, too!

One Lesson: Don’t be Too Rigid When it Comes to Your Passions

Hatton's early understanding of the limits of single-minded focus in his chess-playing days offers a vital lesson on the versatility of passions. Too often, we confine ourselves to one pursuit, fearing deviation implies failure. Hatton urges us to embrace diverse interests, recognizing depth in one area doesn't hinder exploration elsewhere. His journey in robotics exemplifies this, where one passion enriches many. It's a reminder to stay open to new paths, fostering adaptable growth and exploration.

One Exercise: Reflecting on Your Unifying Passions

One theme I’ve observed in many of the super passionate people I’ve profiled, Hatton included, is that of the overarching passion that links various other interests. Take some time to reflect on all of your past and current interests and passions. Identify any recurring themes or elements. What might be one or a few unifying themes among them? For example, my unifying themes include human potential, writing, and passion itself. Consider how this insight might help guide your future choices, aligning your actions more closely with your core passions.

One Curiosity: What is the Current State of Robot Dinosaurs?

My conversation with Hatton got me curious: how have robot dinosaurs evolved since that pivotal 2001 MIT article? My curiosity led me down a fascinating rabbit hole, which led me to this article recently published in The New York Times: “Do Not Fear the Robo-Dinosaur, Learn From it.” It features Roboteryx, a turkey-size black robot modeled after Caudipteryx, a small omnivorous dinosaur from 124 million years ago. My answer? Apparently, a lot.

Links