“Something changed that day. I felt stuck for so long. And then I thought, ‘You know what? I can do that. I can take that advice. I can go to the gym and do handstands.’” — Megan Vaughan Giesbrecht

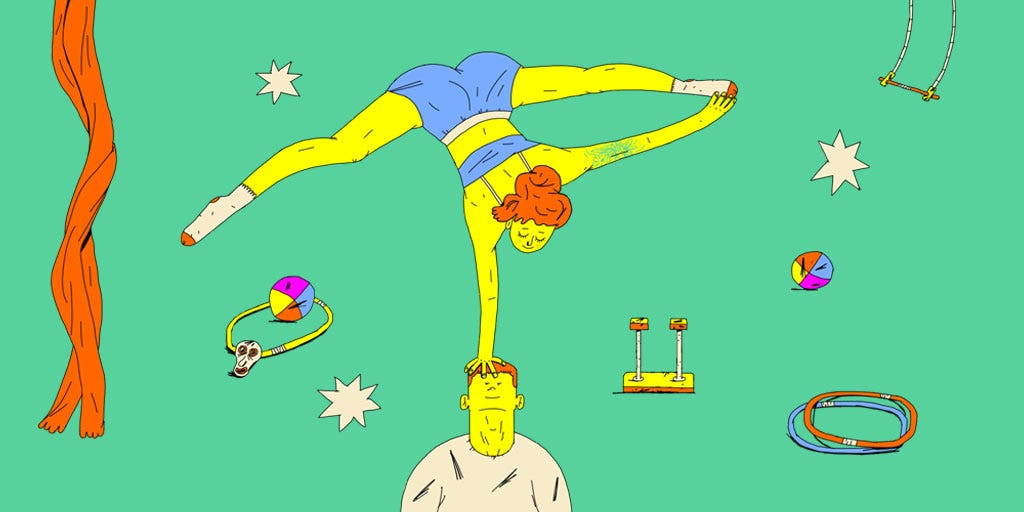

Megan Vaughan Giesbrecht skips across the floor of American Sports Acro and Gymnastics, the gymnastics gym in her hometown of Sonora, California. She jumps onto a pair of handstand canes, her toes pointed high in the air. She stands still in time for a moment and then… a cartwheel into a front split. She waves to her mom who watches from the side of the mat. She is laughing. Glowing even.

“What was your question?” Giesbrecht says, emerging from her nostalgic reverie and returning to the present. She looks around and becomes aware of her surroundings — her therapist’s office, with its dimly lit walls, is enveloped in wood paneling and crammed with books, evoking a feel of a movie set from the seventies.

“When was the last time you remember being happy?”

“I just remembered,” she says. “It was when I was a kid running around in the gym… doing handstands!”

Her therapist doesn’t hesitate.

“Well, my prescription for your depression is simple,” he says. “Do that. I think you should go back to the gym and do handstands.”

At first, Giesbrecht responds with a blank stare. “What kind of advice is that?” she thinks. But then, as she lets the idea sink in, she feels an energy rise within her. He’s onto something, she realizes. “I’m in,” she tells him.

“It was one of the first moments of my life that I can look back and think, ‘something changed that day,’” she tells me in our interview. “I felt stuck for so long. And then I thought, ‘You know what? I can do that. I can take that advice. I can go to the gym and do handstands.’”

And it’s a good thing she did. Today, Giesbrecht is still glowing and still doing handstands. As a matter of fact, as a full-time circus performer, she spends most of her life upside down — exactly as she wants it — working all the tiny gritty details of professional-level handstands, contorting her body in ways most people couldn’t dream of doing. She is a master of the discipline of hand-to-hand, also known as partner or group acrobatics. And six days a week, she mesmerizes crowds of circus goers while balancing on the hands of her porter, Axl.

What lit the original spark? The one that she briefly lost? When Giesbrecht was three, she saw the Magnificent Seven, the 1996 U.S. Olympic women’s gymnastics team that won the first ever gold medal for the U.S. in the women’s team competition. “I told my mom, ‘I want to do that’,” she says.

The only gym in her small town also happened to have a gymnastics program. She started recreational classes, and, at five, began to compete.

“I have some very funny VHS videos of me meandering around a competition floor, literally looking like I'm still wearing diapers. It's very cute,” she says, laughing. Her smile inspires me to smile too — I can’t help it.

As a kid, she would train for up to seven hours a day. But to do gymnastics at that high of level ongoingly, she had to move away from home. Her family didn’t have much money, though, and soon, her passion pursuit became an unbearable financial burden. Gymnastics is an expensive sport. The stress weighed on her until she finally made the decision to go back home and give up her competition career — at age thirteen.

“I never thought I would do gymnastics or handstands ever again,” she says.

Giesbrecht studied with the same devotion she brought to gymnastics, eventually earning a degree in exercise biology at from the University of California, Davis. She loved science and math and thought that she might go into research or medicine. At that time, she had no movement practice of her own.

She did teach kids acrobatics on the side and loved it. Sometimes, she would even do a few handstands with the kids. Yet it never felt like anything she could pursue. “It was just a fun memory,” she says.

After she graduated, she got married and had a daughter named Bird. Yet, she felt stuck. Her future seemed foggy.

“I just got into a really not awesome place,” she says — until, inspired by her therapist’s simple but profound advice, she started training at a gym in Redding, California, where it just so happened that a circus performance team also trained. She began to train with them, just for fun at first, but then more seriously. And so, when the troupe invited her to Paris with them to become part of a well-known cabaret show, she was all in.

“I was like, ‘Sign me up with the circus!’” she says, laughing again. “That’s what I did. It was the first time in so many years I felt like myself.” Returning to her roots was like finding a part of herself she thought was forever lost.

Now Giesbrecht is part of an acrobatics troupe called Gravity & Other Myths, which performs The Mirrorat the Chamäleon theater in Berlin. She will be there for six months before moving on to a new show somewhere else in the world. I ask if this is typical. “Six months is a dream,” she says, explaining that a typical residency is less than two weeks. “It’s kind of the max that you’ll get.”

A typical day? Giesbrecht is up at 6 a.m. to spend time with her daughter and get her off to school. Then she teaches handstand lessons to her students around the world before heading to the theater to train herself for two and a half hours before the show starts. The show, where Giesbrecht flies from Axl’s hands to his head and back again — her hand balancing skills on point — starts at 8 p.m. and lasts for two hours.

But it’s not over yet. After the show, she gathers with the troupe to cool down and give each other notes and feedback for the day. Then she goes home, shovels food into her mouth, teaches more lessons until about 1 a.m. before going to bed and doing it all over again. It’s exhausting, yes — but she wouldn’t have it any other way. She is living the dream.

I got a front-row, upside-down seat to her training regimen — (which you can see on Instagram — when she served as my handstand coach. As she does with all her students, she poured her heart into her work with me. She gave me the most detail-oriented drills to help me refine the nerdy micro-skills I needed to perfect my handstand line and achieve a press-up. She put me on the path to the distant glory of a one-armed handstand. It remains lightyears away for me, and something she does with ease. I know she treats every student this way.

Ultimately, Giesbrecht’s is a story of lost and found — of a small flame from childhood going out but then reigning bigger than ever. She is a reminder to all of us that sometimes the pursuit of passion is not always about looking outward or forward but backward — to those moments as a child that we hoped could last forever. Maybe they can.

But what’s her best advice for those who want to live passionately? She lights up when I ask and explains what she calls the “hermit crab approach to life.”

She likens our growth to hermit crabs, which change shells as they grow, suggesting that we too should embrace each stage of our journey — even if it feels like too small a fit for our big dreams.

“It almost never happens overnight,” she tells me. It’s about those ‘drips’ of achievement — the incremental successes on the way to achieving our goals. “Yes, I got this gig. Yes, I got this handstand. And you feel like you're just waiting for the next drip.”

With each small victory, we edge closer to our dreams. Geisbrecht’s philosophy of passion mirrors, in many ways, the process of handstand mastery. Each attempt, as slow and imperceptible as it may seem, contributes to our long-term progress. The frustration, the determination, the strain accumulates, drip by drip, until one day, all the effort crystallizes. Suddenly, you have mastered the handstand.

To watch Geisbrecht execute a handstand with a grace that seems to defy gravity is to witness the culmination of years of dedication she’s put into her craft. Yet within the spotlight’s glow and the hushed awe of the audience, there is an unmistakable spark in her eyes — the same joy and wonder that lit up the young girl doing handstands in her hometown gym.

Her life now as a professional circus artist may be worlds apart from the carefree days of her youth, but the essence remains the same — a pure love for the art and a burning passion that has only expanded with time.

She has found her perfect shell.

Three takeaways from our conversation:

1. Find your Passion Comeback Story. Geisbrecht's return to gymnastics and acrobatics after years away demonstrates the power of revisiting past passions. Reflect on times when you felt a deep sense of engagement, curiosity, and joy. What were you doing? What stopped you from pursuing it further? What can you do right now to try it again… ideally, within the next 24 hours? Explore local classes or online platforms. Get creative!

2. Seek Professional Insight on Rediscovering Your Passions. When Geisbrecht felt lost, she turned to a therapist, whose simple advice led her to a profound realization and set her on a new path. Often, discussions with therapists or coaches focus on addressing negative feelings, but they can be equally valuable for exploring your untapped interests and aspirations. If you feel stuck or unsure about your direction, a professional can offer a fresh perspective and help you devise strategies to reignite your sense of aliveness.

3. Apply the ‘Drip’ Strategy to Passion Pursuits. Geisbrecht's "hermit crab" approach highlights the importance of valuing small, consistent steps, or ‘drips,’ when in pursuit of our passions. Apply this method to your own passions: if you’re passionate about writing, commit to writing a certain number of words daily; if you’re drawn to music, allocate a small amount of time each day for practice. Celebrate your small victories and understand that every small effort is a step closer to mastering your passion, much like each handstand technique Megan perfected brought her closer to her dream — but often felt too small relative to its full potential.