“Everybody thinks of sand as like some ubiquitous little brown ball. But it turns out sand is a whole story.” — Dr. Gary Greenberg

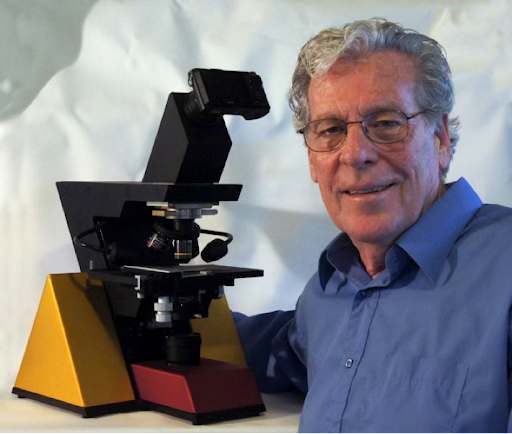

Dr. Gary Greenberg leans in toward the microscope, bringing his eye up to the edge of the lens. He opens it wide. And, as always, the scene now just inches from him takes his breath away. There, on the other end of the microscope is a multi-colored universe just seconds ago invisible made up of infinite shapes, sizes, and textures — like colorful pieces of candy.

It’s “nature’s secret wonder,” as he calls it — a single grain of sand.

“Ordinary things are totally extraordinary when you look through the microscope,” he says. “Every grain of sand is a jewel.”

Greenberg’s life is also extraordinary when we look at it through the microscope. Driven by an insatiable curiosity to look beyond the surface level — a characteristic true, I have found, for so many of the most passionate people — he is one of the world’s pioneers of microphotography and microscopy (for which he holds nearly 20 patents).

But his technological marvels are just of many points of evidence that Greenberg is on fire. He has published two books on exploring our “micro worlds,” especially sand (“yes, there’s that much to say about sand”). He built advanced 3D microscopy technology for the International Space Station. He contributed to capturing the fine details of moon sand brought back by Apollo 11. And he even worked as the lead scientist on the first Superman film, where he naturally used microscopes to turn human pancreatic cells into the cinematic world of the planet Krypton.

He shows that the questions we ask often lead us to the passions we love.

I came across Greenberg’s work while scrolling through science-based TED talks one day to learn and get inspired. As soon as I came across his, I knew I had to talk to him for On Fire.

“What scientists know about the universe is unbelievable,” he tells me in our interview, his gaze drifting as if looking to some distant galaxy. “We know about every atom in our body. We have pictures of the beginning of the universe.”

“But most people have no clue what’s happening.” he continues. “Scientists have a very strange view of the universe. I have a very strange view… of how absolutely extraordinary the universe is.”

Greenberg was 13 when he peered into his first microscope. His dad brought a professional stereo microscope back from Japan. When Greenberg looked into it, he could barely believe his eyes.

“I was just amazed at what you could see,” he says. “It was like a whole world opened up to me.” Greenberg would find bugs and all sorts of things from his family’s garden and look at them under the microscope — and, just like today, found himself mesmerized by a world most people ignored.

Around the same time, his grandfather gave him a complete set of Leonardo da Vinci notebooks complete with all of the drawings. Combined, these two gifts changed him forever.

“I got really interested in learning,” Greenberg says. He didn’t know it when he was younger, but he was dyslexic. And like so many kids with learning differences, he felt left behind. “I didn’t really know that,” he says, remembering his teenage years. “I just knew I couldn’t read very well.”

But the microscope and the da Vinci books were the spark he needed to realize that although he might need to learn differently from others, he did love to learn. “I had to teach myself other ways of learning,” he recalls. “That became part of my life… learning through experiences. And creating the experiences to learn from.”

College, though, was the big lucky break. It was after graduating from University of Southern California with a psychology major that he became fascinated with photography. While Greenberg had grown up in an artistic family and had always loved art, he had struggled to find his medium. Photography was different. He turned his lens toward the overlooked aspects of nature that captivated him.

“Photography really allowed me to express what I see,” he says. “It was an incredible power.”

After graduating USC with a psychology major, Greenberg took his newfound love for photography and joined forces with his brother and a couple of their friends to create a company called Environmental Communications in Venice Beach, California. They made slides, films, and videotapes about art, architecture, and nature and sold them to universities and libraries all over the world. This was before the internet — so creating a place where artists could gather and showcase their work was revolutionary.

During this time, Greenberg also began collaborating with Hollywood, where he applied his scientific expertise to enhance films. He used microscopes to add a layer of scientific authenticity to movie scenes, increasingly incorporating this tool into his work.

“I just got hooked on microscopes,” he says. He got so hooked, in fact, that he followed his passion to London, where he received a PhD in developmental biology and used microscopes to study cell interaction. Then he devoted three more years of his life to post-doctoral study.

Then he started inventing them too.

All throughout his studies, Greenberg had been using microscopes where he says he couldn’t see what he needed to see — everything was flat and there was no contrast. He knew from his work in photography that there was a basic problem with these old-style microscopes and how they were lit. They either had one light coming down — or one light coming straight up.

“I knew as a photographer you’d never shoot a scene that way,” he says. “I mean, just never. You’d bring in key light, fill light, back light. You’d try and highlight what you’re trying to show.”

Greenberg started bringing in his knowledge of photography lighting to microscopes. And the result, he says, was phenomenal.

“You got contrast, better depth of field, and better resolution because of the lighting,” he says. “And the side effect was you could get 3D out of it.”

Greenberg knew he was onto something. He resigned from his academic position and secured an investor to pursue his new obsession. Before long, he had launched Edge-3D, where he made 3D microscopes and sold them all over the world. He spent the next few decades deep in his passion, transforming the field of microscopy.

Then, in his early sixties, he thought maybe it was time for a break. He moved to Maui intending to retire. But things didn’t go quite as planned.

“I’m busier now than I’ve been in my entire life,” he says. He continues to take photos (both regular and microscopic) — while working on multiple new television series and traveling the world to give talks about microscopes, consciousness, and the universe. On top of that, he teaches part-time at a local Hawaiian school — and he is currently working on his twentieth microscope patent.

“I’m working on too many things,” he says, laughing. But he clearly loves it. “I can’t help myself. It’s like I’ve got no choice.”

At eighty, Greenberg has the energy of someone half his age. If I could make one wish, it would be to feel as passionate about life as Greenberg when I reach his age.

So what’s his secret? How does he live a life so clearly on fire?

He looks closer. It’s not just curiosity that defines Greenberg. It’s an extreme form of it that doesn’t stop at surface-level answers and surface-level images.

“It’s all about curiosity,” he says. “Inspiration is about sparking curiosity. That’s the deal.”

So how, then, do we spark our own curiosity? Greenberg keeps his advice simple: get outside.

“I think the old-fashioned way is through nature,” he says. He glances at the window, where the lush greenery of Hawaii seems to be on the verge of spilling into his home, and smiles.

“But most people,” he continues, “are looking at brick walls and have jobs they hate. Nature is the last thing they have time for. But little do they know that a little communing with nature will make their lives much better. So, I’m trying to inspire that idea.”

Greenberg has certainly inspired me. Immediately after our talk, I rode my bike down to the expansive beaches of Venice Beach, California — which I’m lucky enough to call my home. There, I spent the next half hour doing nothing but marveling at the miles of sand in front of me. “Nature’s secret wonder” was now a little less of a secret to me.

Takeaways

Here is one big thing I learned this week about passion, one exercise you can do to stoke your own inner fire, and one aspect of Greenberg’s intense enthusiasm that rubbed off on me — and that I now want to learn more about, too!

One Lesson: Use Images to Make People Fascinated

Greenberg believes that everyone is inherently interested in science; however, the term “science” itself can make some people hesitant. This is one reason he’s turned to art to reveal the often-overlooked wonders of nature, stating, “If you start telling [people] about science, they get turned off immediately. But if you showthem something that fascinates them, that’s the doorway that you can get them to ask, ‘What is that?’” And ifthey get to be fascinated, we know fervor for the topic is suddenly possible on the other side!

One Exercise: Take a Nature Break — and Look Closer

We all understand the benefits of being outdoors — it reduces stress, improves our mood, helps with focus and attention, and can even improve our immune system and physical health. But next time you’re out in nature, don’t just wander with your mind elsewhere. Instead, pay close attention to the details you might normally overlook — the shape of the leaves, the strange appearance of insects on the ground, the patterns of the clouds, and yes, even the sand. You may not have a microscope, but bring a magnifying glass – or just get very close to whatever it is that you are observing. Discover the wonder in the details.

One Curiosity: Sand!

Following my interview with Greenberg, I visited two beaches with remarkably different sand: Venice Beach in California and Miami Beach in Florida. The sand is so different in both places. In Venice, it’s light, golden, and compact, while Miami’s sand is white, powdery, and almost silky, sticking to the skin. Now, I can’t help but wonder what the sand from both places look like under a microscope. And I suspect I won’t look at any beach again without wondering this!

Yes, Miami and Venice sand is quite different. Sand blows and moves across the Atlantic from Africa to North America vice versa. Nothing is ever static. Check out @musee_ephemere another curiosity.